Articles & Chapters – Graphic Narrative

‘The Tension of History: An Interview with Nic Watts and Sakina Karimjee.’ Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics (April 2024), pp.1-13.

Nic Watts and Sakina Karimjee are the co-creators of Toussaint Louverture: The Story of the Only Successful Slave Revolt in History (2023), a graphic novel adapted from a play by the anti-colonial historian C.L.R. James. It tells the story of the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) as a slave-led uprising of world-historical significance. This interview provides in-depth discussion of several aspects of the graphic novel, including its origins and inspiration, the parallels between theatre and comics, the use of graphic narrative to picture world-historical events, and the enduring importance of the Haitian Revolution today. Read more.

‘Graphic Capitaloscenes: Drawing Infrastructure as Historical Form.’ Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 65.4 (2024), pp.680-695.

This article describes “graphic Capitaloscenes” – narrative moments in which graphic novels draw infrastructure as a material expression of capitalism’s historical development. Drawing on work that has described graphic narrative as both an “infrastructural” and “scenographic” form, it contends that graphic novels are particularly adept at representing infrastructure as historical content while themselves materializing that historical infrastructure on the page. Bringing this to bear on visual texts concerned with capitalism’s frontier zones, this article suggests that graphic novels are therefore not only able to stage extractive infrastructures as historical forms, but that they are also themselves formally conjoined to the current historical moment of the Capitalocene. The article offers two case studies in support of its argument, each of which revolves around the extraction of fossil fuels: Joe Sacco’s Paying the Land (2020) and Pablo Fajardo’s Crude, A Memoir (2021). In each of its readings, the article shows how these comics are able to stage infrastructure as historical form, while at the same time bringing into view anti-colonial and anti-capitalist relations that offer a counterpoint to the accumulative relationships of the Capitalocene. Read more.

’Graphic Borders: Refugee Comics as Migration Literature.’ In Gigi Adair, Rebecca Fasselt, & Carly McLaughlin eds., The Routledge Companion to Migration Literature. New York: Routledge, 2024, pp.280-291.

What does it mean to draw a refugee? Why have so many artists sought to tell migrant stories through hand-drawn images in recent years? Why are these drawings or paintings of refugees so often arranged into a sequential order—what we might refer to as “sequential art,” “graphic narratives,” or even “comics”? What are the affordances and politics of these “refugee comics”? Who makes them? Where are they published and how are they read? And what kinds of artistic and narrative techniques have they developed to address the complex representational, political, and cultural questions that structure the relationship between readers and refugees? These are some of the questions addressed in this chapter. Through multiple examples from a range of different genres, forms, and platforms, it aims to give a broad introduction to refugee comics as a substantive and growing contribution to literatures of migration. Read more.

‘Intolerable Fictions: Composing Refugee Realities in Comics.’ In Ralf Kauranen, Olli Löytty, Aura Nikkilä, & Anna Vuorine eds. Comics & Migration: Representation & Other Practices. New York: Routledge, 2023, pp.257-270.

In this chapter I want to argue for a different way of conceptualising the important work that refugee comics do. Rather than emphasising comics as a medium that is somehow an antidote to the prevailing photographic and filmic streams of our hyper-visua media culture, I want to instead shift our attention to their composition and more particularly to the work they do to reconfigure the dominant relationship between image and text. To grasp the full force of this shift, we must unsettle two common misconceptions that are implied by the brief quotation earlier. First is the notion that in our digitised visual culture there are “too many images” of refugees specifically, and of war and displaced people generally. Against this assumption, I would argue that there are not “too many” of these images, and that in fact there is a dearth of them. But there are too many images of unnamed refugees, too many photographs of people contained within the frame and subject to the camera’s gaze, yet deprived of access to accompanying explanatory or self-identifying text. The second and related misconception that I argue we should reconsider is the idea that the veracity and verifiable “truth” of the photographic image is in question, and that its political impact has therefore been diminished. Rather than despairing with postmodernists that the “sign” of the photograph has now utterly fragmented away from the reality it signifies, we might be better served by questioning whether the underlying premise of this notion – which assumes that there should be a direct line between the singular photograph or image of the refugee, on the one hand, and empathetic feeling or political action on the part of the viewer, on the other – is all that helpful in the first place. Read more.

‘Contingent Futures and the Time of Crisis: Ganzeer’s Transmedial Narrative Art.’ Literary Geographies 8.2 (October 2022), pp.154-174.

This article explores the work of the Egyptian street artist and graphic novelist, Ganzeer, who describes himself as a ‘contingency artist’. Developing this idea of contingency, the article shows how Ganzeer’s work responds to the time of crisis as something that is narrated and performed, especially in the era of image capitalism. It begins with a discussion of Ganzeer’s use of street art during the Egyptian Revolution, showing how graffiti strategically emphasised the time of crisis as a momentary rupture in order to connect local political movements with a global media and international viewership. The article then turns to a close reading of Ganzeer’s more recent graphic novel, The Solar Grid (2016-present), to show how the medium of comics allows him to construct more elongated narratives in which the time of crisis is modernity itself. In conclusion, the article reads Ganzeer’s street art and graphic novel together, highlighting their transmedial connections to argue that it is through the revelation of ‘crisis’ as a productive category, rather than an observable condition, that Ganzeer builds contingent and sometimes revolutionary futures. Read more.

‘Pages of Exception: Graphic Reportage as World Literature.’ In James Hodapp ed., Graphic Novels as World Literature. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022, pp.11-31.

I argue in this chapter that graphic reportage unsettles both the “world” and “literature” of “World Literature” in productive and pressingly political ways. With their shared inclusion of spaces of exception, the examples of graphic reportage analyzed here join up stories of otherwise disconnected, isolated, and imprisoned people, from the borders of Fortress Europe to the “Jungle” refugee camp in Calais, and from remote refugee detention centers in Canada to the militarized Mexican border city of Juárez. The artists surveyed in this chapter try to communicate stories from places where the rights-based legal fabric of the nation-state system has been cut away, withdrawn, or denied, and where a carceral humanitarianism has arisen in their place. Just as importantly, each artist uses a shared formal technique to communicate the partial mobilities of the testimonies included in their reportage, thereby insisting on nonfiction as literature, and thus troubling the notion of “literature” itself. Finally, by circulating through di&erent though sometimes connected media spaces, partially online and physically online, these pages of exception come together to form a World Literature that is not smooth or uneven, cosmopolitan or capitalist, but unforgivingly tuned into the carceral spaces that interrupt and fragment our world. Read more.

‘The Gutters of History: Geopolitical Pasts and Imperial Presents in Recent Graphic Non-Fiction.’ In Michael Goodrum, David Hall, & Philip Smith eds., Drawing the Past: Comics and the Historical Imagination in the World. Jackson: Mississippi University Press, 2022, pp.56-78.

The comics addressed in this chapter offer a contrapuntal reading of the colonial present’s Orientalist rhetoric in order to challenge it, while also challenging a tendency to fetishize the imaginative power of the comics “gutter” in much comics criticism. For it is in a contrapuntal sense that I deploy the phrase included in the title of this chapter, “the gutters of history”: the comics’ gutters materialize contrapuntal geographies and histories spatially on the page, thereby accounting for the historical omissions of the colonial present and reinserting them to effectively challenge the West’s contemporary neo-imperial interference in the Middle East. Read more.

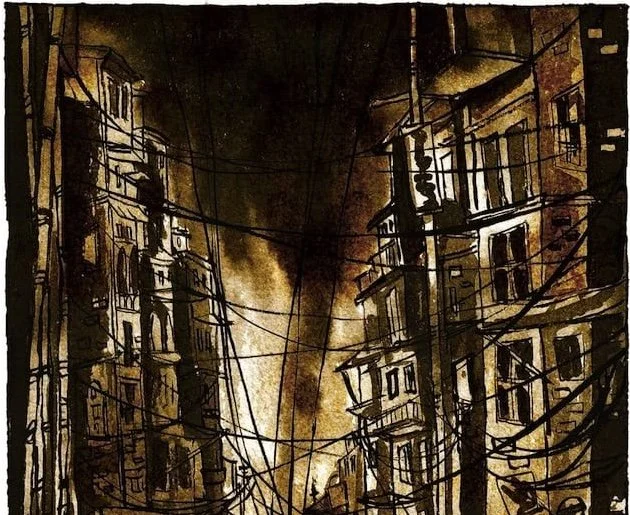

‘Infrastructural Forms: Comics, Cities, Conglomerations.’ In Lieven Amiel ed., Routledge Companion to Literary Urban Studies. New York: Routledge, 2022, pp.163-176.

This chapter responds to the “three D’s” of urbanisation with its own list of “three C’s”: it makes the case for comics as an artistic and narrative form that is particularly capable of capturing the density and dynamism of increasingly global cities, comprising as they both do a complex conglomeration of variously interrelated and unevenly autonomous moving parts. Whether the accumulations of capital that coagulate into points of urban redevelopment and gentrification, for example, or the interstices of slums and favelas that are at different times ignored by and resistant to the state, the unequal spaces of today’s cities are brought into a field of mutual play and narrative position by comics and graphic narratives. This aptitude for arresting the sociospatial dynamics of the city has been described variously as a “spatial form” (Fraser) and an “infrastructural form” (Davies), but as numerous critics have agreed, it is always a distinctly urban form (see Ahrens and Meteling). Comprising narrative building blocks and an architecture all their own, comics are able to intervene into the sociospatial dialectic of urban life (see Soja), not only revealing the infrastructure of the city as a material embodiment of competing and often invisible interests but also recalibrating and reconceiving urban space towards more socially and spatially just ends – often from the ground up. Read more.

‘Witnesses, graphic storytellers, activists: an interview with the KADAK collective.’ Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 12.6 (April 2022), pp.1399-1409.

In this interview, several members of the South Asian womxn’s graphic storytelling collective, KADAK, discuss the group’s recent projects, their collaborative production processes, and the themes that are most central to their work. After a brief introduction, the discussion turns to the benefits and difficulties of self-publishing, working online and offline, and nationally and internationally, and the collective’s first book-length, crowd-funded project, The Bystander Anthology, which was published in 2020. Read more.

With Filippo Menga. ‘Apocalypse Yesterday: Posthumanism and Comics in the Anthropocene.’ Environment and Planning E: Nature & Space 3.3 (August 2020), pp.663-687.

It is widely recognised that the growing awareness that we are living in the Anthropocene – an unstable geological epoch in which humans and their actions are catalysing catastrophic environmental change – is troubling humanity’s understanding and perception of temporality and the ways in which we come to terms with socio-ecological change. This article begins by arguing in favour of posthumanism as an approach to this problem, one in which the prefix ‘post’ does not come as an apocalyptic warning, but rather signals a new way of thinking, an encouragement to move beyond a humanist perspective and to abandon a social discourse and a worldview fundamentally centred on the human. The article then explores how the impending environmental catastrophe can be productively reimagined through graphic narratives, arguing that popular culture in general, and comics in particular, emerge as productive sites for geographers to interrogate and develop posthuman methodologies and narratives. Developing our analysis around two comics in particular – Here and Mad Max: Fury Road – we show how graphic narrative can help us to move beyond the nature–society divide that is rendered anachronistic by the Anthropocene. Read more.

‘Dreamlands, Border Zones, and Spaces of Exception: Comics and Graphic Narratives on the US-Mexico Border.’ a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35.2 (March 2020), Special Issue: Migration, Exile, and Diaspora in Graphic Life Naratives, pp.383-403.

This article explores the connections between the spaces of exception along national borders and the bordered architecture of graphic narratives in Charles Bowden and Alice Leora Briggs’ Dreamland: The Way Out of Juarez (2010) and Jon Sack’s La Lucha: The Story of Lucha Castro and Human Rights in Mexico (2015). Drawn to the US-Mexico border, both of these graphic narratives make visible the routine violence of a nation-state system that devalues human life through the production of spaces of exception—spaces which gather especially at this global regime’s ever-hardening borders. Yet they also begin to make visible—and participate in—the array of spatial practices that challenge the violence these borders inflict, countering a refusal to “see” these spaces and self-reflexively detailing the processes by which the identities of border victims are recovered and documented. Read more.

‘Graphic Katrina: Disaster Capitalism, Tourism Gentrification, and the Affect Economy in Josh Neufeld’s AD: New Orleans After the Deluge.’ Journal of Graphic Novels & Comics 11.3 (2020), pp.325-340.

This article explores the ways in which Josh Neufeld’s documentary comic, A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge, which was published first online from 2007 to 2008 and then collected in book form in 2009, offers a radical visual commentary on the processes of disaster capitalism and tourism gentrification that have reshaped New Orleans since Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Whilst A.D.’s biblical imagery evokes the proto-corporate language of the ‘blank canvas’ in order to critique regimes of disaster capitalism, its vertical multi-scalar perspectives meanwhile resist the racism of media coverage of the event. Through colouring and other aesthetic choices, the comic also challenges the subsequent propagation of an ‘authentic image’ of New Orleans that promotes tourism gentrification. Where previous critics have emphasised the emotional appeal A.D. makes on its readers, I instead discuss the comic’s identification of the structural conditions that have violently impacted the city’s most marginalised inhabitants. Nevertheless, the article qualifies these contentions by acknowledging that A.D. also contributes to an ‘affect economy’ that has exacerbated the privatisation of previously public infrastructure and social services, often to the detriment of pre-Katrina residents simply trying to return to their city. Read more.

‘Infrastructural Violence: Urbicide, Public Space, and Postwar Reconstruction in Recent Lebanese Graphic Memoirs.’ In Ian Hague, Ian Horton, & Nina Mickwits eds., Contexts of Violence in Comics. New York: Routledge, 2020, pp.128-144.

This chapter argues that the cartographic and architectural representations of the city in Ziadé’s and Abirached’s graphic memoirs expose the less visible, though fundamentally embedded, infrastructural violence that both exacerbated and actively participated in the more visible instances of Lebanon’s wartime violence. In so doing, these comics allows us, following Zižek, ‘to disentangle ourselves from the fascinating lure of this directly visible “subjective” violence, violence performed by a clearly identifiable agent,’ to instead perceive the contours of an otherwise ‘invisible,’ structural violence (2008, 1). Published some two decades after the overt violence of the Civil War came to an unstable conclusion, these Lebanese graphic memoirs engage ‘post-memorially’ with the infrastructure space of Beirut’s wartime urban landscape. By foregrounding the deeper spatial and structural violence of the war, they seek first to emphasise how this violence endures in the present, and second, to offer a future-oriented vision of a more inclusive, desegregated post-war city space. Read more.

‘Urban Comix: Subcultures, Infrastructures and “the Right to the City” in Delhi.’ In Alex Tickell & Ruvani Ransinha ed., Delhi: New Literatures of the Megacity. London & New York: Routledge, 2020, Chapter 9.

This article argues that comics production in India should be configured as a collaborative artistic endeavour that visualizes Delhi’s segregationist infrastructure, claiming a right to the city through the representation and facilitation of more socially inclusive urban spaces. Through a discussion of the work of three of the Pao Collective’s founding members – Orijit Sen, Sarnath Banerjee and Vishwajyoti Ghosh – it argues that the group, as for other comics collectives in cities across the world, should be understood as a networked urban social movement. Their graphic narratives and comics art counter the proliferating segregation and uneven development of neo-liberal Delhi by depicting and diagnosing urban violence. Meanwhile, their collaborative production processes and socialized consumption practices, and the radical comix traditions on which these movements draw (and which are sometimes occluded by the label “Indian Graphic Novel”) create socially networked and politically active spaces that resist the divisions marking Delhi’s contemporary urban fabric. Read more.

‘Introduction: Documenting Trauma in Comics.’ In Dominic Davies & Candida Rifkind eds., Documenting Trauma in Comics: Traumatic Pasts, Embodied Histories, & Graphic Reportage. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, pp.1-26.

This introduction unpacks some of the many complex connections between trauma, comics, and documentary form. It begins by theorising trauma as a ‘sticky’ concept that troubles disciplinary boundaries, before suggesting that comics such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1980–1991) have played a significant role in the active production—rather than simply reflection or reification—of cultural and academic conceptions of trauma. It then turns to a critical overview of Caruthian and other hegemonic models of trauma, combining this with brief outlines of each of the book’s chapters to show how they seek to unsettle a dominant ‘trauma paradigm’, or to divert away from a recognised ‘trauma aesthetic’. In its final section, the introduction emphasises the important contributions made by efforts to decolonise trauma studies, exploring how several of this book’s contributors are informed by and continuing this important work, especially through their re-evaluation of the figure of the witness. The introduction concludes by drawing out and reiterating the book’s overarching contention: that comics are a generative force at the core of trauma itself, moulding and melding it into new shapes that might provide new models for working it through in the future. Read more.

‘Crossing Borders, Bridging Boundaries: Reconstructing the Rights of the Refugee in Comics.’ In Elena Fidian-Qasmiyeh ed., Refuge in a Moving World. London: UCL Press, 2020, pp.177-192.

It is into a visual culture, both of imagistic ephemerality and of prevalent anti-migrant sentiment, that comics effectively intervene. In the age of the internet, viewers in the West are trained on a daily basis to make sense of multiple images spliced with pieces of text, as they log onto Facebook feeds or scan through Twitter. Comics, especially those published online (as is the case for these refugee comics), tap into this constant stream of information, harnessing the experience of information transmission and consumption to which viewers are becoming increasingly accustomed (Gardner, 2006). In addition, however, journalism in comics form is able to do two things: first, it can document suffering that goes un-photographed. It imaginatively visualizes oral and written testimonies in order to document human-rights violations, lending them the ‘authenticity’ that contemporary news outlets and consumers demand (Smith, 2011). Second, and perhaps even more importantly, comics’ sequential and highly mediated form offers an antidote to the ‘post-truth’ culture of our contemporary world (Mickwitz, 2016), in which photographs are detached from their original context, circulate at lightning speed through multiple framings and re-framings, and are often mobilized towards dubious political ends. The laboured etchings of comics journalism offer an antidote not only to the lack of visualization but also the decontextualization of photographic images that, in their proliferation, are reduced to insignificance. Read more.

‘Braided Geographies: Bordered Forms and Cross-Border Formations in Refugee Comics.’ Journal for Cultural Research 23.2 (October 2019), pp.123-43.

This article offers a close analysis of a trilogy of ‘refugee comics’ entitled ‘A Perilous Journey’, which were produced in 2015 by the non-profit organisation PositiveNegatives, to conceive of comics as a bordered form able to establish alternative cross-border formations, or ‘counter-geographies’, as it calls them. Drawing on the work of Martina Tazzioloi, Thierry Groensteen, Jason Dittmer, Michael Rothberg and others, the article argues that it is by building braided, multi-directional relationships between different geographic spaces, both past and present, that refugee comics realise a set of counter- geographic and potentially decolonising imaginaries. Through their spatial form, refugee comics disassemble geographic space to reveal counter-geographies of multiple synchronic and diachronic relations and coformations, as these occur between different regions and locations, and as they accumulate through complex aggregations of traumatic and other affective memories. The article contends that we need an interdisciplinary combination of the critical reading skills of humanities scholars and the rigorous anthropological, sociological and theoretical work of the social sciences to make sense of the visualisation of these counter-geographic movements in comics. It concludes by showing how the counter-geographies visualised by refugee comics can subvert the geopolitical landscape of discrete nation-states and their territorially bound imagined communities. Read more.

‘Urban comix: Subcultures, Infrastructures, and “the Right to the City” in Delhi.’ Journal of Postcolonial Writing 43.3 (June 2018), Special Issue: Delhi: Writings on the Megacity, pp.411-430.

This article argues that comics production in India should be configured as a collaborative artistic endeavour that visualizes Delhi’s segregationist infrastructure, claiming a right to the city through the representation and facilitation of more socially inclusive urban spaces. Through a discussion of the work of three of the Pao Collective’s founding members – Orijit Sen, Sarnath Banerjee and Vishwajyoti Ghosh – it argues that the group, as for other comics collectives in cities across the world, should be understood as a networked urban social movement. Their graphic narratives and comics art counter the proliferating segregation and uneven development of neo-liberal Delhi by depicting and diagnosing urban violence. Meanwhile, their collaborative production processes and socialized consumption practices, and the radical comix traditions on which these movements draw (and which are sometimes occluded by the label “Indian Graphic Novel”) create socially networked and politically active spaces that resist the divisions marking Delhi’s contemporary urban fabric. Read more.

‘“Comics on the Main Street of Culture”: Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell, Laura Oldfield Ford’s Savage Messiah, and the Politics of Gentrification.’ Journal of Urban Cultural Studies 4.3 (October 2017), pp.333-361.

Through a comparative discussion of Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell (serialized 1989−96, collected 1999), which is now widely marketed as a ‘graphic novel’, and Laura Oldfield Ford’s more self-consciously subcultural zine, Savage Messiah (serialized 2005 to 2009, collected 2011), this article explores the correlation between the gentrification of the comics form and the urban gentrification of city space − especially that of East London, which is depicted in both of these sequential art forms. The article emphasizes that both these urban and cultural landscapes are being dramatically reshaped by the commodification and subsequent marketization of their subcultural or marginalized spaces, before exploring the extent to which this process neutralizes their subversive qualities and limits democratic access to them. In conclusion, however, the article demonstrates that comics artists tend to collect their ephemeral comics and publish them as marketable graphic novels not to commodify them, nor to maximize their profits. Rather, they do so in order to reach a wider readership and thereby to mobilize their subversive, anti-gentrification political content more effectively, constituting radical urban subcultures that resist the reshaping of London into a segregated and discriminatory cityscape. Read more.

‘Comics Activism: An Interview with Comics Artist Kate Evans.’ The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship 7.1 (November 2017), p.18.

This is an interview with comics artist Kate Evans, author of Red Rosa (2015) and Threads: From the Refugee Experience (2017), as well as a number of other comics, about her recent work, which operates at the intersection of several of the most exciting genre developments in comics in recent years. In the interview Evans reflects on recent shifts in comics journalism, as well as other trends in the field such as the rise of graphic memoir, through examples taken from Evans’s own work as well as that of Joe Sacco, Lynda Barry, Alison Bechdel and others. Read more.

‘Comics Journalism: An Interview with Josh Neufeld.’ International Journal of Comic Art 18.2 (October 2016), pp.299-317.

In this interview, Josh Neufeld talks about the phenomenon of comics journalism, his personal development as an artist and journalist, as well as his book, A.D., and the story behind its creation. He also discusses one of his most recent projects, a comic published in Foreign Policy magazine, entitled ‘The Road to Germany: $2400’, which integrates original reporting by Alia Malek and photographs by Peter van Agtmael to tell the story of Syrian refugees as they attempt to cross into Europe. He reflects on the difficulties and productivities of working collaboratively with other writers and journalists, and some of his current projects and ideas for the future. Read more.