Infrastructure in the Ruins of The Matrix

This short paper was delivered at Panel 707: The Infrastructures of Dystopia, hosted by the Marxism, Literature, and Society Forum at the Modern Languages Association annual conference in San Francisco in January 2023. I post it here, partly because it never found a home anywhere else, and partly because my quiet obsession with The Matrix trilogy is too cringe for me to ever go back and resuscitate the paper for a more meaningful publication. Nonetheless, I still maintain that the film remains a gateway into thinking about 21st-century infrastructure.

The Wachowski’s iconic 1999 sci-fi film, The Matrix, was just one in a wave of reality-breaking films that washed through movie theatres at the turn of the twenty-first century. From The Truman Show, which trapped Jim Carrey in a giant media dome, to Vanilla Sky, which locked a disfigured Tom Cruise into a cryogenic dream, Hollywood developed something of a narrative obsession with white men who suspected that the world in front of them was not all as it seemed. In these movies, a cult of suspicion – perhaps a critique that was about to run out of steam – leads to the protagonist’s discovery of an underworld in which the infrastructures that make modern life possible have been concealed. Within a decade of the Soviet Union’s collapse and Francis Fukuyama’s notorious ‘end of history’ claim, movies like The Matrix were already registering the tensions thrown up by liberal democracy’s inbuilt contradictions. As the likes of Clinton and Blair were privatising infrastructure and removing it from the public sphere, the seeds of the psychic dislocation and political disempowerment that would lead to Brexit and Trump were beginning to make themselves felt in these films. As the British critic Mark Fisher would later put it, while ‘memory disorder provides a compelling analogy for the glitches in capitalist realism, the model for its smooth functioning would be dreamwork.’

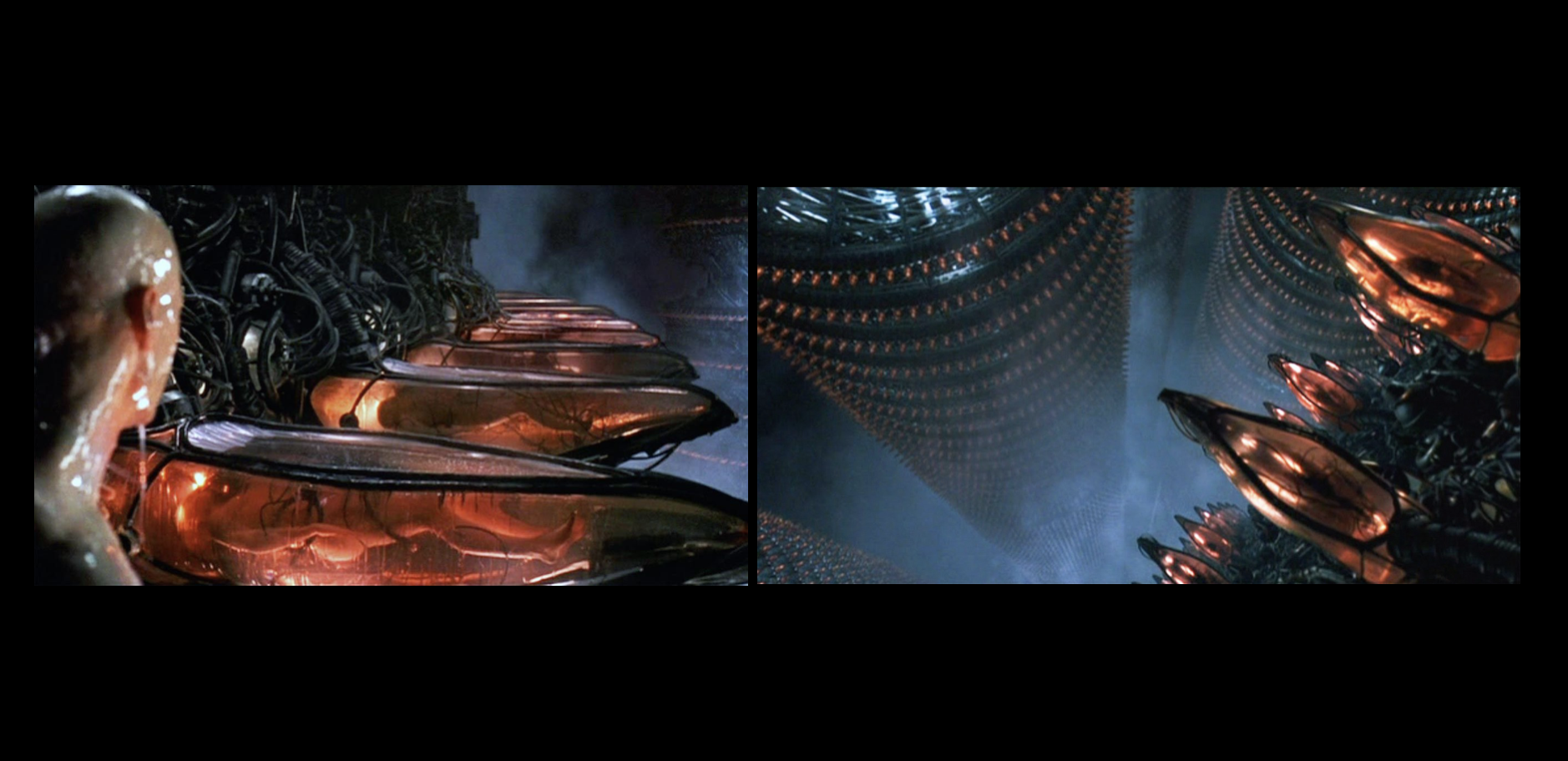

The Matrix begins in what looks like the late twentieth century – ‘the pinnacle of human civilisation,’ as Morpheus describes it – but the film soon reveals this reality to be little more than a dreamworld created by the movie’s eponymous computer programme. Behind this illusionary software, humans are in reality enslaved, their bodies functioning as battery power for the same artificially intelligent robots that designed the Matrix to keep them subdued. The plot follows Mr Anderson, later Neo (played by Keanu Reeves), as he is offered an opportunity to take ‘the red pill’, ‘unplug’ from the Matrix, and ‘wake up’ to reality, the film heightening its message with imagery and language borrowed from the history of plantation slavery and the underground railroad. As a somewhat belaboured allegory of Marxist alienation, the manufactured world of the Matrix programme stands in for neoliberalism’s perpetual present, while behind the smooth surface of reality as it is immediately presented to us resides a future of human slavery, environmental destruction, industrial-style infrastructure, and the continuation of History with a capital ‘H’.

What’s confusing about the future world of The Matrix is that while it’s obviously dystopian, it’s also strangely desirable. Once the apocalyptic reality has been revealed, the majority of characters would much rather be in that future than the simulation of 1990s: the Wachowski’s make very clear aesthetic and casting choices designed to make their dystopian world feel more authentic, more caring, more human, more real. In so doing, the film suggests that it is precisely the removal of historical struggle from reality and the reduction of the world to the ‘atemporal utopia’ of liberal democracy that has reduced us all to the ‘passive state of living batteries.’ Counterintuitively, what the film reveals as its dystopian reality – a dis-alienated underworld where we all work on real infrastructure with our own human hands – is therefore in fact the very object of our utopian longing. The film’s juxtaposition of illusion and reality therefore has to be flipped around: as Slavoj Zizek puts it, ‘what the film renders as the scene of our awakening into our true situation, is effectively its exact opposition, the very fundamental fantasy that sustains our being.’ Taking this further, I think we can be more precise still: insofar as this fantasy borrows cultural imagery from a ‘great’ industrial past, the film presents less a utopia or dystopia and something more like a nostalgia: The Matrix is nostalgic for the socialist future that was lost with the rise of neoliberalism to global hegemony.

Everyone always baulks when I confess this, but my favourite film in the trilogy is actually the second, The Matrix Reloaded. It is not a better movie than the first, but because it’s exempt from the tighter necessities of explanation and plot, it allows some of the franchise’s more philosophical questions room to breathe. There’s a particularly revealing conversation between Neo, our superhero protagonist, and Councillor Hamann, a governor of the city of Zion. It takes place in the ‘real’ world, in the engine room where the light, oxygen, and heat is produced for the subterranean city that provides refuge for those who have been freed from the Matrix. It’s worth reproducing more or less in full here:

Councillor Hamann: Almost no one comes down here, unless of course there’s a problem. That’s how it is with people, nobody cares how it works, as long as it works. I like it down here. I like to be reminded this city survives because of these machines. These machines are keeping us alive while other machines are coming to kill us. Interesting, isn’t it? The power to give life and the power to end it.

Neo: We have the same power.

Hamann: Well, I suppose we do. But down here I sometimes think about all those people still plugged into the Matrix, and when I look at these machines I can’t help thinking that in a way we are plugged into them.

Neo: But we control these machines, they don’t control us… If we wanted, we could shut these machines down.

Hamann: Sure, that’s it, you hit it, that’s control isn’t it. If we wanted we could smash them to bits. Although if we did we would have to consider what would happen to our lights, our heat, our air.

Neo: So we need machines and they need us. Is that your point, Councillor?

Hamann: No, no point… There is so much in this world that I do not understand. See that machine? It has something to do with recycling our water supply. I have absolutely no idea how it works, but I do understand the reason for it to work. I have absolutely no idea how you are able to do some of the things you do, but I believe there is a reason for that as well.

In this discussion of infrastructure, Councillor Hamann momentarily brings back into view the democratic politics that successive rounds of privatisation and financialisation had eviscerated through the neoliberal era. He begins by recognising the fundamentally social and interdependent nature of human existence. As he explains, individual members of a society do not need to understand how everything works, they just need to agree that they should. As a councillor, Hamann knows better than most that the political sphere is where this is debated and agreed. This is, quite simply, social democracy, where infrastructure works as what Bonnie Honig calls a ‘public thing’: it is the stuff that ‘brings us together in ways that are not optional’ and which act as a ‘“holding environment” of democratic citizenship.’ As I’ve already implied, I think Zion – the utopian/dystopian world at the centre of The Matrix – wants to be read as that brief exception in the history of capitalist development known to most as the mid-twentieth-century welfare state.

But what’s more interesting about this scene is that, in almost the very same breath, Hamann betrays these democratic forms of direct governance for what can only be described as the false promise of the neoliberal dreamworld. Under Zion’s socialist arrangements, humans have collectively ensured that the water recycling plant keeps working; they don’t all know how it works, but they’ve agreed that it should. Yet within the totality of the film, this democratic socialism is not a satisfactory end to history; it cannot resolve capitalism’s contradictions. Instead, Hamann can only find salvation in Neo’s supernatural powers, as he agrees to forfeit the democratic space of the Council of Zion to one individual leader who promises to resolve all of our problems, so long as we believe in him: politics is reduced to a question of faith. Although humans are locked into an historic class struggle with the machines in these movies, it’s not their collective endeavours but Neo’s supernatural abilities that eventually secures their freedom. Thus does The Matrix briefly throw into question, but then ultimately concede to, the dominant ideology of its time. In its narrative oscillations between the dreamworld of the Matrix and the apocalyptic world of Zion, it models the formal continuities between neoliberal individualism and the strains of authoritarianism that would grow into a world of Donald Trumps and Boris Johnsons, not to mention a motley crew of infrastructure-obsessed tech billionaires.

There are some concerning genealogies when we track these narratives as they unfold in the ‘real’ world on our side of the cinema screen. The language of The Matrix films became central to a series of aggressively masculinist movements. Most obvious here is the infamous online Reddit community, ‘The Red Pill’, a hateful male complaint site at the heart of the so-called ‘manosphere’, and a key platform for the ‘men’s rights’ movement and the normalisation of deeply misogynistic and sexualised attitudes to women, both online and offline. This spawned an array of revanchist cultural phenomena, from the figure of the ‘incel’ (the involuntarily celibate) to public intellectuals such as Jordan Peterson (the pseudo-psychologist of white male self-help) to far-right terrorists such as Anders Breivik (the Norwegian racist and anti-feminist who murdered 77 people in 2011). In the US, several perpetrators of mass-shootings have shortened their sentences by claiming that they committed their crimes because they believed they were inhabiting a simulated reality – this is a legal manoeuvre now known as ‘the Matrix defence.’ Meanwhile, tech bro Elon Musk has gone on record with his belief that we’re not living in a ‘base reality’ but in an actual Matrix, a massive ‘simulation’ created by a species ‘more advanced’ than our own.

The Matrix therefore did not merely simulate neoliberalism’s contradictions. It actually helped to produce a culture that sees ‘supernatural’ individuals, from politicians to billionaires, as the only viable way of constructing and controlling the vast infrastructure systems on which our everyday lives depend. This is at once neoliberalism’s hollowing out of the democratic state and its authoritarian pseudo-solution. To put it in Councillor Hamann’s terms, the political space where the reason for this or that infrastructure might be debated has so narrowed that politics itself has become meaningless, divorced from worthwhile infrastructural change. All that remains is an infrastructure of speculation and increasingly of spectacle, as authoritarian figures promising investment in imaginative and often nostalgic infrastructures – ‘make America great again’ – gain electoral ground over the development of a meaningful programme of infrastructure that actually works.

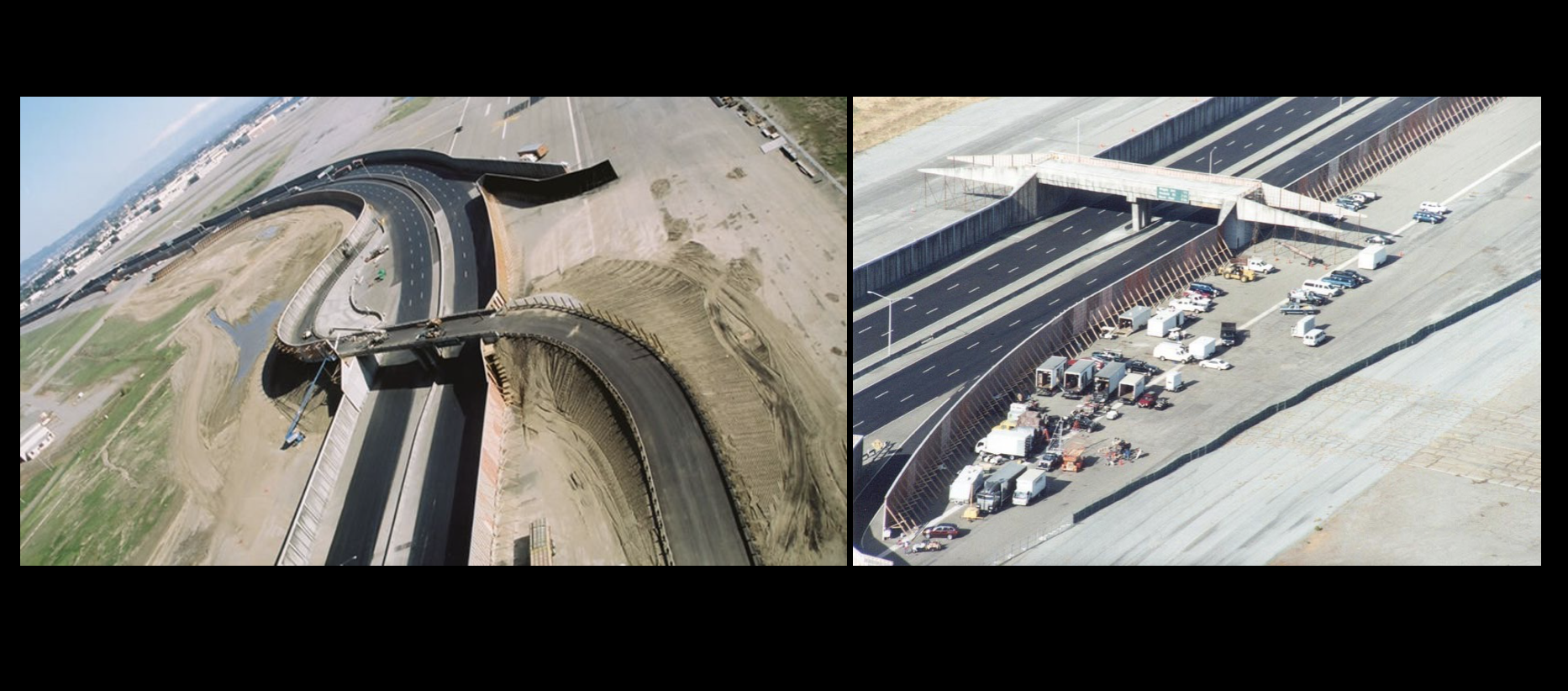

As though to cement this very point, in 2001 the Wachowski’s built an entire freeway on a disused naval base in the middle of the Californian desert at a cost of $2.5 million. The stretch of six-lane tarmac was a little over a mile in length, with six-metre high walls hemming it in on all sides. Though constructed to look like concrete, these walls were actually made from timber and plywood, designed not as safety barriers to keep vehicles in but to block the ‘real’ world out of the movie’s fictional frame. It was an entirely self-contained space that did not begin or end anywhere – it was quite literally a road to nowhere. The only function of this infrastructure was to provide the setting for one of the most celebrated scenes in twenty-first-century Hollywood cinema: the famous ‘freeway chase’ that forms the centrepiece of the The Matrix Reloaded. When filming was completed in 2002, the road and surrounding wall were dismantled and the wooden materials sent to Mexico, where they were recycled to build low-income housing. In the US, such materials were only good for the production of media spectacle; across the border to the South, they could be used to build fundamental infrastructure for sustaining human life.

The Matrix Reloaded introduces the iconic freeway scene with ominous dialogue:

Trinity: You always told me to stay off the freeway.

Morpheus: Yes, that’s true.

Trinity: You said it was suicide.

Morpheus: Then let us hope that I was wrong.

Morpheus is so afraid of the freeway because he knows it is a road to nowhere; or to put it another way, he knows it’s almost certainly a dead end. As an enclosed hyper-space of total mobility, it is at once the fantasy of capital and the system’s ultimate demise. The road obtains its value not from any practical use, but as a spectacle for pure exchange. It’s a kind of triple allegory, modelling first the Matrix programme, then the rise of speculative finance, and finally the Hollywood film itself. As homologous spectacles, the freeway models the fictional Matrix as an enclosed dreamworld behind which a ‘real’ reality is concealed; the Matrix models the cinematic experience of the movie, as audiences sit inside theatres while history rages on outside; and the cinematic experience models the rise of neoliberal finance, as infrastructure is transformed from a functional necessity into a dreamworld of pure commodity exchange.

Yet these comparisons do also show how the metaphysical fabric of each stacked reality is always cracking open and breaking onto something else. This is the ‘glitch’ in the Matrix of unfettered growth: the freeway scene ends with a head-on crash; the Matrix programme crashes and must be rebooted; The Matrix franchise crashes with its bombing box-office comeback film, Matrix Resurrections; and finance capital crashes with the collapse of the housing market in 2008. Of course, despite the efforts of movements like Occupy and more recently of Bernie Sanders and then Biden, these crashes have done little to return infrastructure from private to public spheres: governments bailed out the banks, austerity was unleashed, and now our real-world infrastructure is mostly owned by the Musks and Bezoses of this world. Indeed, if there is hope in the story that The Matrix has modelled for us, it is not in the global North. Rather than utopia, dystopia, or nostalgia, we might instead read The Matrix universe as an allegory of global cores and peripheries. The road to nowhere did end up somewhere after all: its parts were sent to the slums of the South, where their use-value was meaningfully restored through their recycling into public housing infrastructure. Perhaps, as the dystopian writer J.G. Ballard once remarked, ‘the periphery is where the future reveals itself.’